‘I LOOK AT DANCERS BUT I SEE PEOPLE’

An interview with Natália Horečná

Eva Gajdošová ‘Horečná’s work is profound and shows the full potential of dance. When united with dramaturgy and adequate staging, dance can be life changing. Grigorovich understood that and gave that gift to John Neumeier, and it lives on in Horečná.’

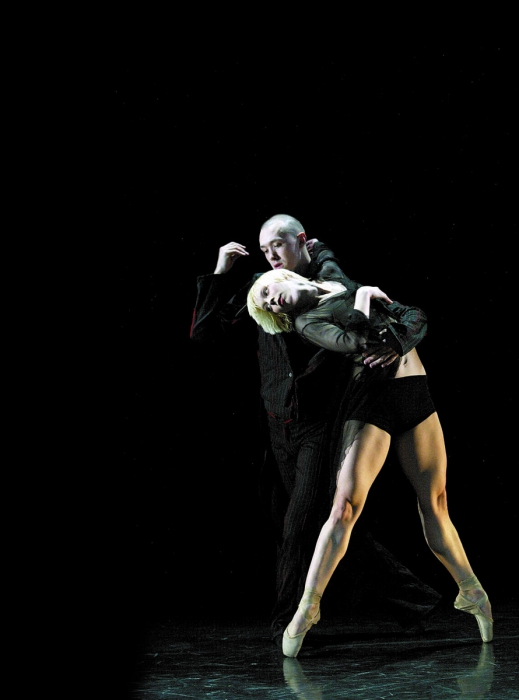

Ballet-Hommage Forsythe | Horecna | Lander at Vienna Staatsoper

‘The combination of Horečná’s dramatic movement repertoire, visceral dancing, and the intricacy of her narratives makes each of her choreographies a captivating experience for all theatregoers. The physical and emotional aspects of each show are amplified by a minimalist scenography, which consists of suggestive lighting and simple costumes that do not draw attention away from the dancers’ breathing bodies. The choreographer’s existential themes stand in contrast to her straightforward and amiable nature. Horečná is a spontaneous, beautiful woman who has much to say, and who is always surrounded by dancers and colleagues. Only few artists enjoy as much popularity. Honesty. Optimism. Respect for the craft and for the performers. Natália Horečná is undoubtedly on the brink of a great international career.’

Pavol Juráš, Operaplus

“I learnt from the past and I cherish it. Today, I live for the present. My life is choreography.”

Natália Horečná

If we were to go back in time and begin to map out your life decade by decade, who are the people that have influenced you the most in each given period?

When I was in first grade, a teacher came to our school. Her name was Mrs. Boudová, she was from an art school, and she asked if anyone wanted to sign up for ballet class. I immediately ran home to my mother and insisted that she sign me up. Mum often remembers that day with laughter. That was the beginning of my career. Mrs. Boudová later encouraged me to continue my studies at a conservatory, where I met many great teachers and was fortunate enough to be tutored by Mrs. Klára Škodová and Mrs. Skácelová. They both fought so that I wouldn’t have to do folk dance, which, for a while, was a real possibility. They unflinchingly insisted that I should do ballet, and finally, they succeeded. I am forever indebted to them. It’s thanks to them that I can do my profession; it’s thanks to them that I’ve got to where I am today.

Moving on to my time at the conservatory, there was my English teacher, Robert Meško. At school, he helped me enter a competition in Lausanne. I didn’t speak English at the time. Immediately after arriving in Lausanne, where I danced a variation from Giselle, I met the dancers and teachers from Hamburg. Robert told me that they had really liked my performance. I didn’t make the podium the first time around, but the following year, I received the Journalists’ Award and was given 600 Francs, which was a lot of money at the time. Robert knew the director of Hamburg Ballet, Marianne Kruuse, and he arranged an audition for me. I went and I was accepted! Six months later, I was dancing with John Neumeier’s company. That was one of the happiest moments of my life. I remember how I was running down the street, ecstatic. My parents couldn’t afford to pay the monthly fees, so Robert pleaded that the school give me a scholarship, which I eventually received. I wouldn’t have made it without him. I really owe him a lot.

In Hamburg you met John Neumeier.

John Neumeier was my mentor, boss, and choreographer, and we remain friends to this day. Over the nine years that I spent with his company, he taught me a great deal. I suppose I must have been quite wild for him, but we’ve always had a great relationship, and we still do. I am currently planning to present my third production for his junior ballet. Another person who has influenced my life and career is Jiří Kylián. Even while I was dancing at Neumeier’s, I was pining for a placement at the Nederlands Dans Theater. At that time, however, it wasn’t easy. They rarely had any free spots, and when they did, they mostly recruited dancers from NDT 2. Moreover, Glenn, the director, told me that I was too classical for them. I decided to stay in the Netherlands and auditioned for Scapino Ballet Rotterdam, which at the time was headed by choreographer Eda Wubbe. Three years later, the director of the Nederlands Dans Theater rang me up and said, ‘Get over here, we have a spot for you’. I'm glad to have experienced the last years of NDT under the direction of Jiří Kylián. It was a great honour for me to dance in Memoires dʼoubliets, the last choreography he designed for the theatre.

How would you summarise the nine years you spent with John Neumeier?

I learnt to perceive ballet not just as an art form, but as something of a medium which carries a certain message. Dancers, I think, are the conveyers of that message. The great thing about that time was that I learnt to be completely honest with myself, both as a person and as a performer. I had to find out to what degree I could be truthful with others and, more importantly, with myself. If I was ever going to be authentic on stage, I had to be authentic in my personal life. I learnt that on stage we didn’t need any props in order to be authentic. It was important not to pretend, to perform each movement and gesture with ease and sincerity, and to invest ourselves in every character. On my path to this realisation I had the best teachers and choreographers, such as Kevin Haigen, Robert Cohen, Suki Shorer, Marianne Kruuse, Ingrid Glindeman, and others. I perfected my technique. As regards the conservatory that I had graduated from, I must say they had prepared me extremely well. I absorbed new styles and techniques with ease, such as the Balanchine technique, the Bournonville method, the Graham technique, and many others. I learnt a lot from various schools. What stuck with me the most is John’s sentence, ‘Always dance like it was the last performance of your life’. His company was full of strong personalities. Neumeier knew what he could get from people and how to get it from them. He is a great psychologist.

What is the essence of his genius?

He’s a very thoughtful person, endowed with the deepest love for what he does and for people, for human existence. You can see that in his ballets – they are all very profound and intense works. The first Neumeier ballet I ever saw was Ondine. I didn’t sleep the whole night after seeing it, and I still think it’s one of his most powerful ballets. The Lady of the Camellias, Manon Lescaut, Ondine, Swan Lake, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream – everywhere you look, there’s a combination of genius and depth, understanding and being. I still learn from John. Whenever I’m in Hamburg, I sit down in the rehearsal room with a notepad and a pen, and I take notes. I love watching his rehearsals. The last time I staged my choreography in Hamburg, he came to my rehearsals. It was great. He gave me comments and pointers, excellent feedback regarding the visual side of things, the dramaturgy, and the whole setup of the show. I am glad that he likes my work. Our meetings are always very warm, we always hug. He likes to say that ‘there’s no pretence’ to my choreographies. ‘It’s all authentic’. At my last show, which I staged with the Junior Ballet in Hamburg, he even cried. It was a short ballet about children who’ve died in wars – a very difficult theme.

How would you describe Jiří Kylián’s approach to choreography?

Jiří Kylián is a proponent of absolute simplicity, especially when it comes to expression. He wants his dancers to rely only on movement, which, in his mind, has the potential to express everything, even emotions. Kylián approaches choreography in a rather abstract way. When we were performing narrative ballets with Neumeier, we had to act out sadness or sickness, like in the Lady of the Camellias. With Kylián I learnt to express everything through movement. Kylián, he’s all about abstraction, aesthetics, melancholy, and pure beauty. He's definitely a melancholic and also a purist. Purity and perfection define his every ballet. It’s very difficult to work with him, especially with my kind of temperament. He often had to put the brakes on me; he would say, ‘That’s a bit over the top, dear’. His approach is first and foremost that of a perfectionist.

When did you first feel the urge to design choreographies?

No-one today will believe me, but I never really wanted to be a choreographer. Until I was 25 I never felt the need to create. People around me – my boyfriend, father and others – were trying to convince me to give it a try, but I never really had the confidence. I designed my first choreography in 2007, and ever since I haven’t been able to stop. It was love at first sight. I had dabbled in choreography before, when I was with Neumeier, but I didn’t really know what I wanted to say at the time. At NDT I got my chance. I seized it and never let it go. When I designed my first choreography, I was so excited that I could barely sleep. I felt that I could never do anything else, I had so many ideas. And so, every year, I would design a ten, fifteen-minute choreography for the dancers from NDT 2 or NDT 1, which I then presented, first at choreography workshops and then on stage. Later I got my first offers from theatres.

Do you have a preferred composer with whom you collaborate?

Oh yes – that would be Terry Riley, an American composer and the father of minimalism. I'd always liked his music so I sent him some of my works. He was excited and wrote me a letter where he called my ballets ‘gems’. We recently met in Amsterdam, where he was headlining a festival of minimalist music. We have a beautiful relationship. We call each other ‘Cosmic Father’ and ‘Cosmic Daughter’.

Who else is in your team?

The great lighting designer Mario Ilsanker who has done the lighting for all my shows. We are completely in sync. Usually he begins by filming the dance material, then we sit down together, agree on the timing, discuss which lights come at what time, and then he creates the atmospheres. We work on a level where we barely even have to talk to each other. It’s similar with my costume designer Christiane Devos, with whom I’ve done five productions.

Do you have time to follow dancing trends around the world?

To be honest, I don’t. When I work, I don’t allow myself any distractions, and I work almost constantly. I don’t watch TV, I don’t go out or to the theatre, I’m not even on Facebook. When it comes to my work, I don’t look for new styles and techniques. It’s not important to me. The only thing I’m interested in is the human soul. I want to explore as much of it as I can.

How would you describe your dance language?

I work a lot with ballet companies. Most of the dancers have a classical education; they perform in classical shows, and I try not to ‘break’ them, I try to push them forward. But I have always built on neoclassicism. My take is just a bit more visceral and dirty. It often uses voices, gestures, and rudimentary movement. Sometimes it’s brutal and unrestrained, and sometimes we have to freeze and just stand still. As a choreographer, I try to lay bare what’s inside us so that we can embrace our mistakes and vices, learn to love ourselves, get to know the darkness within us so that we can reach light. I owe a lot to darkness. Without it, I would never have known light.

You have a very strong relationship with your dancers.

I love dancers and I have complete respect for their work. I always insist that they connect with the audience, and the only way to do that is by being sincere. It’s all about respect. I look at dancers but I see people; I do theatre with people. Sometimes I ask the dancers to do very demanding stuff on stage, so I work with them individually, behind closed doors. Sometimes it’s difficult, but thankfully, I’ve never had a dancer refuse to do something. They can tell that I respect and cherish their work. I appreciate them for their involvement, for their love of what they do and their courage to open up. Sometimes they love what they do more than they love themselves. I try to balance that out. I need them to accept themselves, because if you don’t love yourself, you cannot give love to others.

Our interview takes place during a workshop with the dancers of the Slovak National Theatre Ballet Company, with whom you are preparing a show featuring the music of Peter Breiner. Do you usually hold workshops before embarking on a new project?

I like to tell stories and create characters with my ballets. Workshops allow me to get a sense of the dancers and the ideal casting. In the beginning, I don’t give the dancers too much space. I want them to adopt my material. I need to know how they view my style and whether they can identify with it. That is how I cast people for the individual characters. Later I give them space to bring in something of themselves. I love the process of our getting to know each other, and I’m happy when people slowly reveal themselves to me and I get to see what’s inside them.

Your home is now in The Hague.

The whole of Europe is my home! I respect every country I work in. Each has its specifics – somewhere it’s the humour, elsewhere it’s the light or smells. I respect the people and the customs of every country. In The Hague, I have enough space for work and leisure. I have my quiet, which I’m starting to find I need more and more of. Ever since my father died [the cinematographer Pavol Horečný, Ed.], I’ve come to realise many things.

What do you take from your father?

An impulsiveness that I often have to rein in. Sometimes it really shines through. And then professionalism, love for what I do, and the ability to see things through the lens of a film camera. Where art was concerned, my father was always my greatest role model. As a cinematographer and director, he had an uncanny sense for lighting and atmosphere, as well as for timing, which is so crucial in both film and theatre. He had a deep understanding of all sorts of art. I learnt a lot from him. He taught me to respect art and to be sincere. He used to say that on camera everyone is transparent and everything shows. One day I would like to make a dance film with my sister, a director, and walk in our father’s footsteps.

What is your definition of art?

Art, to me, is a higher form of communication. It’s something of a fifth dimension, a higher mission, whereby we can touch the human soul. We can change so much. Art can heal people. But they need to be honest with themselves, accept themselves, smile, and accept others, all in spite of the trials and tribulations which life inevitably brings. We always have two options – we can either succumb to hardship or learn to cope with it. We must try not to judge, only to embrace. Art, to me, is an absolutely transcendental component of being.

Natália Horečná was born in 1976 in Bratislava. In 1994 she graduated from the Eva Jaczova Dance Conservatory and then spent a year studying at John Neumeier’s Hamburg School of Ballet. She was a soloist with Hamburg Ballet until 2003. During that time, she starred in a variety of roles, such as Ericlea and Circe in Ulysses, a solo in Magnificat (original choreography for Sylvia Guillem), in Manon Lescaut, in the Lady of the Camellias, and Magdalene in Messiah. She also had roles in other ballets, such as Romeo and Juliet, The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Hamlet, Cinderella, Giselle, Bernstein Dances, Illusions like Swan Lake, Mahler’s 3rd Symphony, Nijinsky, Winter Journey, St. Matthew’s Passion, and others.

Following her departure from Hamburg, Horečná danced with Scapino Ballet Rotterdam; later, until 2012, with Nederlands Dans Theater 1. In her six years with NDT, she starred in shows by many of the world’s greatest choreographers, such as Jiří Kylián, Sol León and Paul Lightfoot, William Forsythe, Mats Ek, Wayne McGregor, and Jacopo Godani.

She currently works with companies such as the Vienna State Ballet, the Helsinki Ballet, the Monte Carlo Ballet, the Royal Danish Ballet, the National Youth Ballet in Hamburg, the Slovak National Theatre Ballet Company, and others. She has designed twenty-eight original ballet choreographies. In 2012, she was nominated for the Choreographer of the Year Award by the ballet critics of Tanz Jahrbuch. That same year, on the occasion of a state visit to Belgium by Slovak President Ivan Gašparovič, she was invited to the Royal Banquet by Queen Beatrix. In 2014, Horečná made the cover page of the prestigious German magazine Tanz, and in September that year, she won the Taglioni Award for Best Young European Choreographer, courtesy of the Vladimir Malakhov Foundation.